Industry pushes for $1B for TMF in ‘Phase 4’ coronavirus stimulus bill

Industry experts argued Monday that the coronavirus pandemic presents Congress with a chance to exceed annual allocations and invest in the Technology Modernization Fund (TMF) at a level that will enable multi-agency IT improvements.

Testifying before the House Government Operations Subcommittee, Matthew Cornelius said Congress and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, who previously served as the House Oversight Committee’s ranking member, should ensure the TMF receives $1 billion in the next coronavirus relief bill. Negotiations on that “Phase 4” bill are expected to intensify this week.

The Alliance for Digital Innovation executive director said only then can the Office of Management and Budget and the General Services Administration shift from supporting agency-specific IT projects to governmentwide ones. The TMF — housed within GSA and overseen by that agency and OMB — gives agencies money for long-term IT modernization projects, but it has struggled to win attention from Congress.

“Frankly, outside of an emergency situation like this, where Congress can go above and beyond the 302(b) allocations that they have on the normal [fiscal year] appropriation cycle, you’re never going to get that amount of investment that is necessary so that OMB and GSA and agencies can really start to transform the government’s IT,” Cornelius said.

In Cornelius’ time with OMB, government could only make “small-bore” project delivery decisions because the TMF received a “wildly inappropriate” $150 million over three years for about 50 projects costing $600 million.

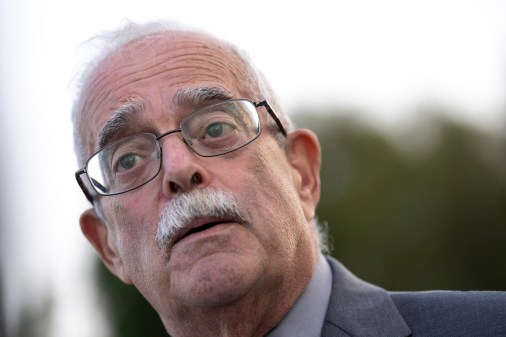

The Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act submitted by House Democrats currently proposes $1 billion for TMF. The last TMF appropriation of $25 million was “simply meaningless,” said Rep. Gerry Connolly, D-Va., the subcommittee’s chairman.

“Modern, reliable IT is not just a nice thing to have,” Connolly said. “Our federal government’s consistent failure to prioritize IT modernization and program delivery prevented the public from receiving the assistance Congress authorized to help the nation weather one of the worst global pandemics in 100 years.”

For example, the Small Business Administration still hasn’t provided a “full postmortem” on timeouts of its E-Tran system, tasked with processing applications for $750 billion in pandemic-related loans, nor has the IRS delivered tens of millions of economic impact payments, Connolly said.

Legislative fixes

Lawmakers like Connolly want agencies to retire legacy systems in favor of new commercial technologies more quickly and are attempting to give them the tools legislatively.

Included in the first group of amendments to the National Defense Authorization Act, which came to the House floor on Monday, is the FedRAMP Authorization Act. The legislation would codify and fund the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program, which helps agencies quickly adopt new cloud services.

Congress can do more by overhauling laws to include metrics for cloud adoption, FedRAMP authorization and reuse, and acquisition of commercial items. The Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act established a commercial-first framework for new technology, but commercial-off-the-shelf systems continue to take a backseat to “bespoke, agency-specific” systems at many agencies, Cornelius said.

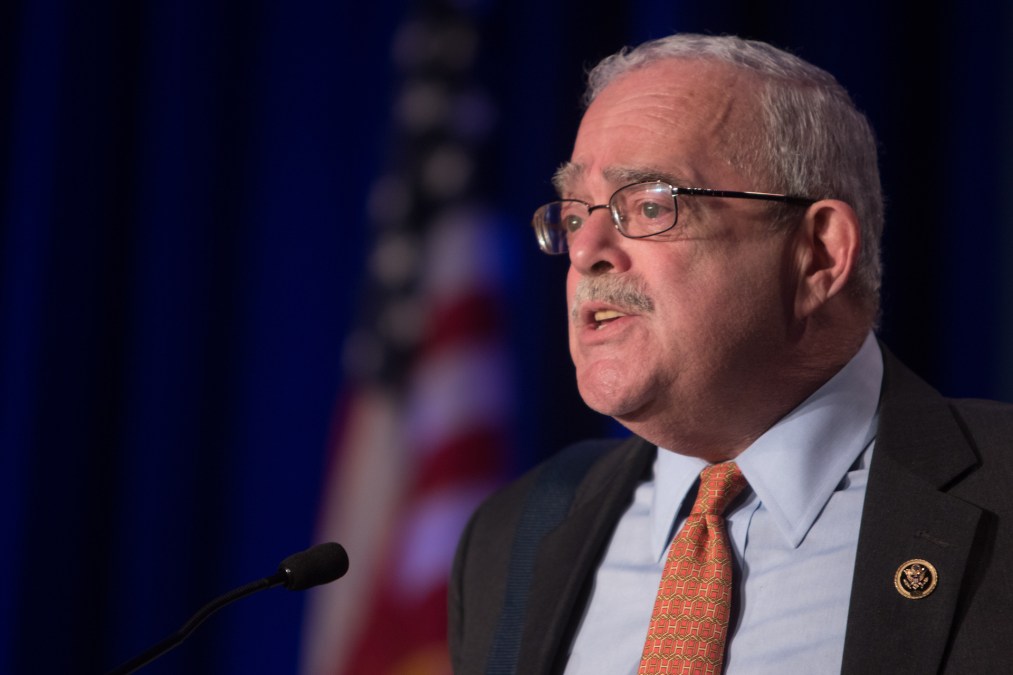

“The issue is that everybody is an IT worker, and the mission users they know what they want,” said Gordon Bitko, senior vice president of policy at the Information Technology Industry Council. “And what they frequently want is not the commercial product but something that’s been customized in some way, and the result when that happens is you take a lot of time taking the commercial product and customizing it into something that then becomes a legacy system that’s difficult to maintain and support.”

Bitko, who previously served as the FBI’s chief information officer, said the agency’s time and attendance system started out as a commercial offering but was customized for congressional reporting and internal use. Upgrades now take months or years to develop in ways that prevent the system from “catastrophically failing,” and it still runs on a restricted network — making it inaccessible from outside an FBI office.

The Department of Justice began data center consolidation in 2014, which included constructing a new center inside an existing Idaho facility. The request for proposals was posted in October 2016, groundbreaking occurred a year later, and the center opened in November with plans be fully operational in September 2020. The center is already outdated, Bitko said.

“Government’s limited technical and contract expertise, risk aversion, process inefficiencies, unpredictable funding, and inflexible construction processes all contribute to timelines much longer than commercial best practices,” Bitko said. “At the same time the lack of multi-year modernization funding ensures legacy applications endure.”