At SXSW, HHS outlines the stumbling blocks to sharing data

The Department of Health and Human Services’ CTO sees the open data movement as a “baton” in a relay race.

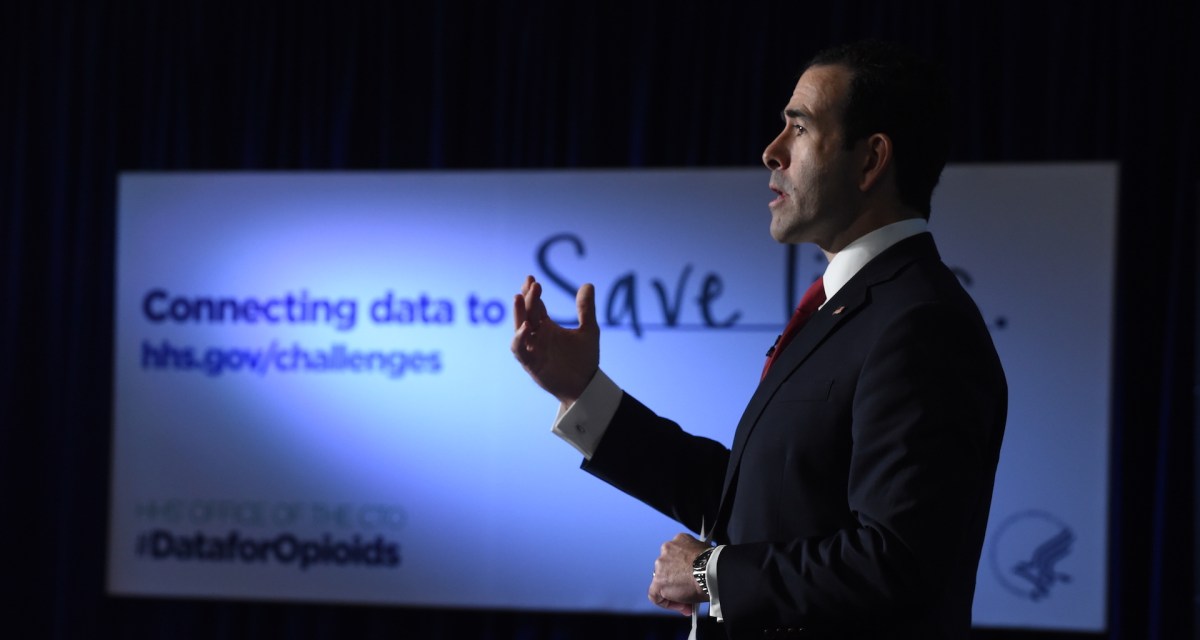

Passing from the Obama administration to the Trump administration, “if it doesn’t get handed off carefully, at full speed, somebody trips up a little bit or drops the baton, we lose a lot of momentum,” Bruce Greenstein said last week at South by Southwest in Austin.

While Greenstein stressed the importance of sharing data during a panel discussion, he and a colleague also didn’t mince words when describing the stumbling blocks the department faces in negotiating the sharing of data within government or outside of it.

“We’ve got to really run hard,” Greenstein said. “We don’t share nearly enough data from within government and clearly not outside of government, on health and issues that impact health.”

One difficulty is proving data’s value to people not typically “steeped in the data space,” said Mona Siddiqui, chief data officer at HHS.

“If you are not familiar with that space from a leadership perspective, when we say let’s use data to make decisions, that phrase doesn’t necessarily translate,” she said.

Certain data sets were opened in the last administration, but it’s hard to quantify the value that work generated, Siddiqui said.

There are also other impediments to the open data, or data sharing, movement, such as statutory ones, Siddiqui explained.

“I think it’s very important to go in a very granular way into the impediments as people see them,” she said. “And sometimes they don’t see them as impediments to data sharing, they see them as the considerations that help them to get the data that they need and as protecting the privacy of individuals that are contributing that data. They think of themselves as stewards of individual data, and it’s important for us to understand that perspective.”

At HHS, Siddiqui’s team is trying to go through the department’s different data assets to understand their full lifecycle. That work includes looking at things like how the data was collected, and what agreements were signed to get it.

“We don’t have all of the data that we need to make our decisions,” she said. “A lot of the data that we collect, we collect it because of congressionally mandated things that need to get reported, not necessarily because we have a great question and then we really deliberately thought about the metrics that need to get collected.”

On top of that, health outcomes are dependent, she added, on many non-health-related metrics. That means partnerships are necessary with other departments to get data that’s necessary to actually make decisions.

“And I would love to explore partnerships with private entities that are collecting data,” she added.

Siddiqui also said she wanted to work with stakeholders – such as members in the audience at the conference – to figure out the most interesting data sets for the public, or what they would like to see released the most.

But releasing data sets to the public is sometimes a complicated endeavor because HHS is often a secondary collector of the data, Greenstein said.

“Most of the data that we work with is not ours, so therefore it is not easy to make public because we’re under contract with, say, 50 states and several territories,” Greenstein said.

And there could be backlash if the public misunderstood data fields and made incorrect comparisons of states’ data in what was made public, Greenstein said. If the data released isn’t high quality and someone misinterprets it, then states might not voluntarily submit the data anymore, he fretted.

“When we’re secondary collectors, we have a relationship to manage and we’re always wanting to learn more on how to make those relationships more fruitful and productive, and maintain our very important, respectful relationship,” he said.

Siddiqui presented another potential roadblock to any kind of secondary uses for data: the original agreement made with the person whose data was collected.

When it comes to data on illicit drug use and related health information, for example, Siddiqui said the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has concerns that response rates could drop if the sensitive data is used in ways other than what was described to the person when it was first collected.

It’s important, she said, to understand the entire chain of the data, and that includes the initial consent given by the person whose data was collected.